Papal infallibility

Papal infallibility is the dogma in Roman Catholic theology that, by action of the Holy Spirit, the Pope is preserved from even the possibility of error[1] when he solemnly declares or promulgates to the universal Church a dogmatic teaching on faith or morals as being contained in divine revelation, or at least being intimately connected to divine revelation. It is also taught that the Holy Spirit works in the body of the Church, as sensus fidelium, to ensure that dogmatic teachings proclaimed to be infallible will be received by all Catholics. This dogma, however, does not state either that the Pope cannot sin in his own personal life or that he is necessarily free of error, even when speaking in his official capacity, outside the specific contexts in which the dogma applies.

This doctrine was defined dogmatically in the First Vatican Council of 1870. According to Catholic theology, there are several concepts important to the understanding of infallible, divine revelation: Sacred Scripture, Sacred Tradition, and the Sacred Magisterium. The infallible teachings of the Pope are part of the Sacred Magisterium, which also consists of ecumenical councils and the "ordinary and universal magisterium". In Catholic theology, papal infallibility is one of the channels of the infallibility of the Church. The infallible teachings of the Pope must be based on, or at least not contradict, Sacred Tradition or Sacred Scripture. Papal infallibility does not signify that the Pope is impeccable, i.e.., that he is specially exempt from liability to sin.

In practice, popes seldom use their power of infallibility, but rely on the notion that the Church allows the office of the pope to be the ruling agent in deciding what will be accepted as formal beliefs in the Church.[2] Since the solemn declaration of Papal Infallibility by Vatican I on July 18, 1870, this power has been used only once ex cathedra: in 1950 when Pope Pius XII defined the Assumption of Mary as being an article of faith for Roman Catholics. Prior to the solemn definition of 1870, Pope Pius IX, with the support of the overwhelming majority of Roman Catholic bishops, had proclaimed the Immaculate Conception of Mary an ex cathedra dogma in December 1854.

Conditions for papal infallibility

Statements by a pope that exercise papal infallibility are referred to as solemn papal definitions or ex cathedra teachings. These should not be confused with teachings that are infallible because of a solemn definition by an ecumenical council, or with teachings that are infallible in virtue of being taught by the ordinary and universal magisterium. For details on these other kinds of infallible teachings, see Infallibility of the Church.

According to the teaching of the First Vatican Council and Catholic tradition, the conditions required for ex cathedra teaching are as follows:

- 1. "the Roman Pontiff"

- 2. "speaks ex cathedra" ("that is, when in the discharge of his office as shepherd and teacher of all Christians, and by virtue of his supreme apostolic authority….")

- 3. "he defines"

- 4. "that a doctrine concerning faith or morals"

- 5. "must be held by the whole Church" (Pastor Aeternus, chap. 4)

For a teaching by a pope or ecumenical council to be recognized as infallible, the teaching must make it clear that the Church is to consider it definitive and binding. There is not any specific phrasing required for this, but it is usually indicated by one or both of the following:

- a verbal formula indicating that this teaching is definitive (such as "We declare, decree and define..."), or

- an accompanying anathema stating that anyone who deliberately dissents is outside the Catholic Church.

For example, in 1950, with Munificentissimus Deus, Pope Pius XII's infallible definition regarding the Assumption of Mary, there are attached these words:

Hence if anyone, which God forbid, should dare willfully to deny or to call into doubt that which We have defined, let him know that he has fallen away completely from the divine and Catholic Faith.

An infallible teaching by a pope or ecumenical council can contradict previous Church teachings, as long as they were not themselves taught infallibly. In this case, the previous fallible teachings are immediately made void. Of course, an infallible teaching cannot contradict a previous infallible teaching, including the infallible teachings of the Holy Bible or Holy Tradition. Also, due to the sensus fidelium, an infallible teaching cannot be subsequently contradicted by the Catholic Church, even if that subsequent teaching is in itself fallible.

In July 2005 Pope Benedict XVI asserted during an impromptu address to priests in Aosta that: "The Pope is not an oracle; he is infallible in very rare situations, as we know."[3]

It is the opinion of the majority of Catholic theologians that the canonizations of a pope enter within the limits of infallible teaching. Therefore, it is considered certain by this majority of theologians, that such persons canonized are definitely in heaven with God. However, this opinion of infallibility of canonizations has never been definitively taught by the Magisterium. Other theologians, even those of earlier times, refer to this majority opinion, as a "pious opinion, but merely an opinion". Before the height of Middle Ages, saints were created not by the Bishop of Rome, but by the bishops of the local dioceses, confirming or rejecting the acclamation of the people calling for declaration of sanctity of a particular Christian person who died "in the odour of sanctity". In Catholic teaching, diocesan bishops do not in themselves possess the charism of infallibility (but do so when gathered in ecumenical council), leaving these early Church canonizations without certainty of infallibility.

Ex cathedra

In Catholic theology, the Latin phrase ex cathedra, literally meaning "from the chair", refers to a teaching by the pope that is considered to be made with the intention of invoking infallibility.

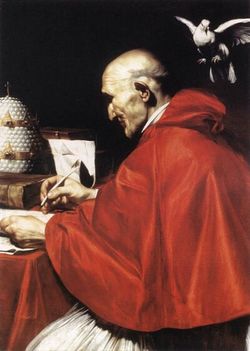

The "chair" referred to is not a literal chair, but refers metaphorically to the pope's position, or office, as the official teacher of Catholic doctrine: the chair was the symbol of the teacher in the ancient world, and bishops to this day have a cathedra, a seat or throne, as a symbol of their teaching and governing authority. The pope is said to occupy the "chair of Peter", as Catholics hold that among the apostles Peter had a special role as the preserver of unity, so the pope as successor of Peter holds the role of spokesman for the whole church among the bishops, the successors as a group of the apostles. (Also see Holy See and sede vacante: both terms evoke this seat or throne.)

Scriptural support for infallibility of the Pope

Believers of the church doctrine claim that their position is historically traceable[4] to Scripture:

- John 1:42, Mark 3:16 ("And to Simon he gave the name "Peter", "Cephas", or "Rock")

- Matthew 16:18 ("thou art Peter; and upon this rock I will build my church; and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it"; cf. Matthew 7:24-28, (the house built on rock)

- Luke 10:16 ("He that heareth you, heareth me; and he that despiseth you, despiseth me; and he that despiseth me, despiseth him that sent me.")

- Acts 15:28 ("For it hath seemed good to the Holy Ghost and to us, ...") ("the Apostles speak with voice of Holy Ghost")

- Matthew 10:2 ("And the names of the twelve apostles are these: The first, Simon who is called Peter,...") (Peter is first.)

- Ludwig Ott points out the many indications in Scripture that Peter was given a primary role with respect to the other Apostles: Mark 5:37, Matthew 17:1, Matthew 26:37, Luke 5:3, Matthew 17:27, Luke 22:32, Luke 24:34, and 1 Corinthians 15:5 (Fund., Bk. IV, Pt. 2, Ch. 2, §5).

Primacy of the Roman Pontiff

Doctrine-based religions evolve their theologies over time, and Catholicism is no exception: its theology did not spring instantly and fully formed within the bosom of the earliest Church.

The doctrine of the Primacy of the Roman Bishops, like other Church teachings and institutions, has gone through a development. Thus the establishment of the Primacy recorded in the Gospels has gradually been more clearly recognised and its implications developed. Clear indications of the consciousness of the Primacy of the Roman bishops, and of the recognition of the Primacy by the other churches appear at the end of the 1st century. L. Ott[5]

Pope St. Clement of Rome, c. 99, stated in a letter to the Corinthians: "Indeed you will give joy and gladness to us, if having become obedient to what we have written through the Holy Spirit, you will cut out the unlawful application of your zeal according to the exhortation which we have made in this epistle concerning peace and union" (Denziger §41, emphasis added).

St. Clement of Alexandria wrote on the primacy of Peter c. 200: "...the blessed Peter, the chosen, the pre-eminent, the first among the disciples, for whom alone with Himself the Savior paid the tribute..." (Jurgens §436).

The existence of an ecclesiastical hierarchy is emphasized by St. Stephan I, 251, in a letter to the bishop of Antioch: "Therefore did not that famous defender of the Gospel [Novatian] know that there ought to be one bishop in the Catholic Church [of the city of Rome]? It did not lie hidden from him..." (Denziger §45).

St. Julius I, in 341 wrote to the Antiochenes: "Or do you not know that it is the custom to write to us first, and that here what is just is decided?" (Denziger §57a, emphasis added).

Catholicism holds that an understanding among the Apostles was written down in what became the Scriptures, and rapidly became the living custom of the Church, and that from there, a clearer theology could unfold.

St. Siricius wrote to Himerius in 385: "To your inquiry we do not deny a legal reply, because we, upon whom greater zeal for the Christian religion is incumbent than upon the whole body, out of consideration for our office do not have the liberty to dissimulate, nor to remain silent. We carry the weight of all who are burdened; nay rather the blessed apostle PETER bears these in us, who, as we trust, protects us in all matters of his administration, and guards his heirs" (Denziger §87, emphasis in original).

Many of the Church Fathers spoke of ecumenical councils and the Bishop of Rome as possessing a reliable authority to teach the content of Scripture and tradition. However, patristic support for papal infallibility does not exist. Theologians of the Middle Ages are responsible for that development.

Theological history

Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages and the Renaissance the doctrine of papal infallibility first developed.

The first theologian to systematically discuss the infallibility of ecumenical councils was Theodore Abu-Qurrah in the 9th century.

In the year 1075, Pope Gregory VII asserted 27 statements regarding the powers of the papacy in Dictatus Papae: "22.That the Roman church has never erred; nor will it err to all eternity, the Scripture bearing witness."

Several medieval theologians discussed the infallibility of the pope when defining matters of faith and morals, including Thomas Aquinas and John Peter Olivi. In 1330, the Carmelite bishop Guido Terreni described the pope’s use of the charism of infallibility in terms very similar to those that would be used at Vatican I.

Dogmatic definition of 1870

The infallibility of the pope was thus formally defined in 1870, although the tradition behind this view goes back much further. In the conclusion of the fourth chapter of its Dogmatic Constitution on the Church Pastor aeternus, the First Vatican Council declared the following, with bishops Aloisio Riccio and Edward Fitzgerald dissenting:[6]

| “ | We teach and define that it is a dogma Divinely revealed that the Roman pontiff when he speaks ex cathedra, that is when in discharge of the office of pastor and doctor of all Christians, by virtue of his supreme Apostolic authority, he defines a doctrine regarding faith or morals to be held by the universal Church, by the Divine assistance promised to him in Blessed Peter, is possessed of that infallibility with which the Divine Redeemer willed that his Church should be endowed in defining doctrine regarding faith or morals, and that therefore such definitions of the Roman pontiff are of themselves and not from the consent of the Church irreformable.

So then, should anyone, which God forbid, have the temerity to reject this definition of ours: let him be anathema. (see Denziger §1839). |

” |

|

— Vatican Council, Sess. IV , Const. de Ecclesiâ Christi, Chapter iv |

||

According to Catholic theology, this is an infallible dogmatic definition by an ecumenical council. Because the 1870 definition is not seen by Catholics as a creation of the Church, but as the dogmatic revelation of a Truth about the Papal Magisterium, Papal teachings made prior to the 1870 proclamation can, if they meet the criteria set out in the dogmatic definition, be considered infallible. Ineffabilis Deus is an example of this.

The British statesman, Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone publicly attacked Vatican I, stating that Roman Catholics had "forfeited their moral and mental freedom". He published a pamphlet called The Vatican Decrees in their Bearing on Civil Allegiance in which he described the Catholic Church as "an Asian monarchy: nothing but one giddy height of despotism, and one dead level of religious subservience". He further claimed that the Pope wanted to destroy the rule of law and replace it with arbitrary tyranny, and then to hide these "crimes against liberty beneath a suffocating cloud of incense".[7] Cardinal Newman famously responded with his Letter to the Duke of Norfolk. In the letter he argues that conscience, which is supreme, is not in conflict with papal infallibility—though he toasts "I shall drink to the Pope if you please--still, to conscience first and to the Pope afterwards".[8] He stated later that “the Vatican Council left the Pope just as it found him”, satisfied that the definition was very moderate, and specific in regards to what specifically can be declared as infallible[9]

Lumen Gentium

The Dogmatic Constitution Lumen Gentium of the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council, which was also a document on the Church itself, explicitly reaffirmed the definition of papal infallibility, so as to avoid any doubts, expressing this in the following words:

| “ | This Sacred Council, following closely in the footsteps of the First Vatican Council, with that Council teaches and declares that Jesus Christ, the eternal Shepherd, established His holy Church, having sent forth the apostles as He Himself had been sent by the Father;(136) and He willed that their successors, namely the bishops, should be shepherds in His Church even to the consummation of the world. And in order that the episcopate itself might be one and undivided, He placed Blessed Peter over the other apostles, and instituted in him a permanent and visible source and foundation of unity of faith and communion. And all this teaching about the institution, the perpetuity, the meaning and reason for the sacred primacy of the Roman Pontiff and of his infallible magisterium, this Sacred Council again proposes to be firmly believed by all the faithful. | ” |

Instances of papal infallibility

It is incorrect to hold that doctrine teaches that the Pope is infallible in everything he says. In reality, the invocation of papal infallibility is extremely rare.

Catholic theologians agree that both Pope Pius IX's 1854 definition of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception of Mary, and Pope Pius XII's 1950 definition of the dogma of the Assumption of Mary are instances of papal infallibility, a fact which has been confirmed by the Church's magisterium.[10] However, theologians disagree about what other documents qualify.

Regarding historical papal documents, Catholic theologian and church historian Klaus Schatz made a thorough study, published in 1985, that identified the following list of ex cathedra documents (see Creative Fidelity: Weighing and Interpreting Documents of the Magisterium, by Francis A. Sullivan, chapter 6):

- "Tome to Flavian", Pope Leo I, 449, on the two natures in Christ, received by the Council of Chalcedon;

- Letter of Pope Agatho, 680, on the two wills of Christ, received by the Third Council of Constantinople;

- Benedictus Deus, Pope Benedict XII, 1336, on the beatific vision of the just prior to final judgment;

- Cum occasione, Pope Innocent X, 1653, condemning five propositions of Jansen as heretical;

- Auctorem fidei, Pope Pius VI, 1794, condemning seven Jansenist propositions of the Synod of Pistoia as heretical;

- Ineffabilis Deus, Pope Pius IX, 1854, defining the Immaculate Conception;

- Munificentissimus Deus, Pope Pius XII, 1950, defining the Assumption of Mary.

For modern-day Church documents, there is no need for speculation as to which are officially ex cathedra, because the Vatican's Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith can be consulted directly on this question. For example, after Pope John Paul II's apostolic letter Ordinatio Sacerdotalis (On Reserving Priestly Ordination to Men Alone) was released in 1994, a few commentators speculated that this might be an exercise of papal infallibility.[11] In response to this confusion, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith has unambiguously stated, on at least three separate occasions,[12][13][14] that Ordinatio Sacerdotalis although not an ex cathedra teaching (i.e., although not a teaching of the extraordinary magisterium), is indeed infallible, clarifying that the content of this letter has been taught infallibly by the ordinary and universal magisterium.[15]

The Vatican itself has given no complete list of papal statements considered to be infallible. A 1998 commentary on Ad Tuendam Fidem, written by Cardinals Ratzinger (the later Pope Benedict XVI) and Bertone, the prefect and secretary of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, listed a number of instances of infallible pronouncements by popes and by ecumenical councils, but explicitly stated (at no. 11) that this was not meant to be a complete list.[14]

The number of infallible pronouncements by ecumenical councils is significantly greater than the number of infallible pronouncements by popes.

Opposition to the doctrine of papal infallibility

Various scripture and history-based arguments

Those opposed to papal infallibility provide various arguments, such as those cited by Geisler and MacKenzie[16] with proof texts for papal infallibility being contended against.[17]

- White[18] and others disagree that Matthew 16:18 refers to Peter being the Rock, based on linguistic grounds, and their understanding that his authority was shared. They argue that in this passage Peter is in the second person ("you"), but that "this rock" is in the third person, referring to Christ, (the subject of Peter's truth confession in the verse 16, and the revelation referred to in v. 17), and who is uniquely and explicitly affirmed to be the foundation of the church.[19] Certain Catholic authorities, such as John Chrysostom and St. Augustine, are cited as supporting this understanding, with Augustine stating, "On this rock, therefore, He said, which thou hast confessed. I will build my Church. For the Rock (petra) is Christ; and on this foundation was Peter himself built".[20]

- The "keys" in the Matthean passage and its authority is understood as primarily or exclusively pertaining to the gospel.[21]

- The prayer of Jesus to Peter, that his faith fail not, (Luke 22:32) it is not seen as promising infallibly to a papal office, which is held to be a late and novel doctrine.[22]

- While recognizing Peter's significant role in the early church, and initial brethren-type leadership, it is contended that the Book of Acts manifests him as inferior to the apostle Paul in his level of contribution and influence, with Paul becoming the dominant focus in the Biblical records of the early church, and the writer of most of the New Testament (receiving direct revelation), and having authority to publicly reprove Peter.(Gal. 2:11-14)

- Geisler and MacKenzie also see the absence of any reference by Peter referring to himself distinctively, such as the chief of apostles, and instead only as "an apostle," or "an elder" (1Pet. 1:1; 5:1) as weighing against Peter being the supreme and infallible head of the church universal, and indicating he would not accept such titles as the Holy Father.

- The Roman Catholic claim that the Lord's commission to Peter to "feed my lambs" in John 21:15ff requires infallibility is seen to be a serious overclaim for the passage.

- The argument based on the revelatory function connected to the office of the high priest Caiaphas, (Jn. 11:49-52) which holds that this establishes a precedent for Petrine infallibility, is rejected, based (among other reasons), on the Catholic-acknowledged position that there is no new revelation after the time of the New Testament, inferred by Rev. 22:18[23]

- Likewise, it is also held that a Jewish infallible Magisterium did not exist, though the faith yet endured, and that the Roman Catholic doctrine on infallibility is a new invention.[24][25]

- The promise of papal infallibly is seen violated by certain popes who spoke heresy (as recognized by the Roman church itself) under conditions which, it is argued, fit the criteria for infallibility.[26][27]

- The condemnation of Pope Honorius I for teaching heresy by the sixth, seventh and eighth ecumenical councils argue against the position that papal infallibility has always been a consistent teaching of the Catholic Church. The counter argument is that Honorius, as Pope Leo II made it clear, was anathematized, not because of heresy, but because of his negligence.

- Regarding the first ecumenical council at Jerusalem, Peter is not seen being looked to as the infallible head of the church, with James exercising the more decisive leadership, and providing the definitive sentence.[28] Nor is he seen elsewhere being the final and universal arbiter about any doctrinal dispute about faith in the life of the church.[29]

- The conclusion that monarchical leadership by an infallible pope is needed and existed, is held as unwarranted on scriptural and historical grounds. Rather than appeal to an infallible head, the scriptures are seen as being the infallible authority.[30][31] Rather than an infallible pope, church leadership in the New Testament is understood as being that of bishops and elders, denoting the same office.[32][33] (Titus 1:5-7)

- It is further argued that the doctrine of papal infallibility lacked universal or widespread support in the bulk of church history, contrary to the claims made by Vatican 1 in first promulgating it,[34] and that substantial opposition existed from within the Catholic Church, even at the time of its official institution, testifying to its lack of scriptural and historical warrant.[35][36][37]

Internal opposition to the doctrine of papal infallibility

Following the first Vatican Council, 1870, dissent, mostly among German, Austrian, and Swiss Catholics, arose over the definition of Papal Infallibility. The dissenters, holding the General Councils of the Church infallible, were unwilling to accept the dogma of Papal Infallibility, and thus a schism arose between them and the Church. Many of these Catholics formed independent communities in schism with Rome, which became known as the Old Catholic Churches.

A few present-day Catholics, including priests, refuse to accept papal infallibility as a matter of faith, such as Hans Küng, author of Infallible? An Inquiry, and historian Garry Wills, author of Papal Sin. A recent (1989–1992) survey of Catholics from multiple countries (the United States, Austria, Canada, Ecuador, France, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, Peru, Spain and Switzerland), aged 15 to 25 showed that 36.9% accepted the teaching on papal infallibility, 36.9% denied it, and 26.2% said they didn't know of it. (Source: Report on surveys of the International Marian Research Institute, by Johann G. Roten, S.M.) Küng has been sanctioned by the Church and prohibited from teaching theology.

Lord Acton, a leading Roman Catholic 19th century British historian, the who succeeded Newman as the editor of the Catholic periodical The Rambler, is justly famous for his axiom, that "Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely. . . There is no worse heresy than the fact that the office sanctifies the holder of it", which he made in a letter to the Anglican Bishop of London, Mandell Creighton, specifically in reference to his opposition to the definition of papal infallibity.

Historical objections to the teachings on infallibility often appeal to the important work of Brian Tierney, Origins of Papal Infallibility 1150-1350 (Leiden, 1972). Tierney comes to the conclusion, "There is no convincing evidence that papal infallibility formed any part of the theological or canonical tradition of the church before the thirteenth century; the doctrine was invented in the first place by a few dissident Franciscans because it suited their convenience to invent it; eventually, but only after much initial reluctance, it was accepted by the papacy because it suited the convenience of the popes to accept it".[38] (See also Ockham and Infallibility). The Rome-based Jesuit Wittgenstein scholar Garth Hallett argued that the dogma of infallibility was neither true nor false but meaningless; see his Darkness and Light: The Analysis of Doctrinal Statements (Paulist Press, 1975). In practice, he claims, the dogma seems to have no practical use and to have succumbed to the sense that it is irrelevant.

In the nineteenth century, before the 1870 definition, two catechisms in use in Ireland explicitly denied the doctrine of Papal Infallibility. In answer to the question of whether the pope was infallible they suggested that such an idea was a Protestant invention made to discredit Roman Catholics. After the formal declaration of the Pope's Infallibility by Pius IX, this question and answer were quietly dropped in subsequent editions, with no explanation for the change.[39]

It is also argued that since the apostle Peter himself was not regarded as infallible in the Bible, and was corrected—albeit in a matter regarding his personal behavior and failure to live by his own teachings—by the apostle Paul (referenced in Galatians 2:11), that it makes little sense to regard current popes as infallible.

The Catholic priest August Bernhard Hasler provides a detailed analysis of the First Vatican Council, and how the passage of the infallibility dogma was orchestrated.[40] Roger O'Toole identifies the distinctive contributions of Hasler as follows:[41] "

- It weakens or demolishes the claim that Papal Infallibility was already a universally accepted truth, and that its formal definition merely made de jure what had long been acknowledged de facto.

- It emphasizes the extent of resistance to the definition, particularly in France and Germany.

- It clarifies the 'inopportunist' position as largely a polite fiction and notes how it was used by Infallibilists to trivialize the nature of the opposition to papal claims.

- It indicates the extent to which 'spontaneous popular demand' for the definition was, in fact, carefully orchestrated.

- It underlines the personal involvement of the Pope who, despite his coy disclaimers, appears as the prime mover and driving force behind the Infallibilist campaign.

- It details the lengths to which the papacy was prepared to go in wringing formal 'submissions' from the minority even after their defeat in the Council.

- It offers insight into the ideological basis of the dogma in European political conservatism, monarchism and counter-revolution.

- It establishes the doctrine as a key contributing element in the present 'crisis' of the Roman Catholic Church."

Additional voices of opposition are compiled in such works as, Roman Catholic opposition to papal infallibility, (1909), by W. J. Sparrow Simpson.[42]

Position of Eastern Orthodox tradition

The dogma of Papal Infallibility is rejected by Eastern Orthodoxy. Orthodox Christians hold that the Holy Spirit will not allow the whole Body of Orthodox Christians to fall into error[43] but leave open the question of how this will be ensured in any specific case. Eastern Orthodoxy considers that the first seven ecumenical councils were infallible as accurate witnesses to the truth of the gospel, not so much on account of their institutional structure as on account of their reception by the Christian faithful.

Furthermore, Orthodox Christians do not believe that any individual bishop is infallible or that the idea of Papal Infallibility was taught during the first centuries of Christianity. Orthodox historians often point to the condemnation of Pope Honorius as a heretic by the Sixth Ecumenical council as a significant indication. However, it is debated whether Honorius' letter to Sergius met (in retrospect) the criteria set forth at Vatican I. Other Orthodox scholars[44] argue that past Papal statements that appear to meet the conditions set forth at Vatican I for infallible status presented teachings in faith and morals are now acknowledged as problematic (e.g. Exsurge Domine).

Positions by Protestant churches

Anglican churches

The Church of England and its sister churches in the Anglican Communion, having seceded from the Roman Church centuries ago, reject papal infallibility, a rejection given expression in the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion (1571):

XIX. Of the Church. The visible Church of Christ is a congregation of faithful men, in which the pure Word of God is preached, and the Sacraments be duly ministered according to Christ's ordinance, in all those things that of necessity are requisite to the same. As the Church of Jerusalem, Alexandria, and Antioch, have erred, so also the Church of Rome hath erred, not only in their living and manner of Ceremonies, but also in matters of Faith.XXI. Of the Authority of General Councils. General Councils may not be gathered together without the commandment and will of Princes. And when they be gathered together, (forasmuch as they be an assembly of men, whereof all be not governed with the Spirit and Word of God,) they may err, and sometimes have erred, even in things pertaining unto God. Wherefore things ordained by them as necessary to salvation have neither strength nor authority, unless it may be declared that they be taken out of holy Scripture.

Methodism

John Wesley amended the Anglican Articles of Religion for use by Methodists, particularly those in America. The Methodist Articles omit the express provisions in the Anglican articles concerning the errors of the Church of Rome and the authority of councils, but retain Article V which implicitly pertains to the Roman Catholic idea of papal authority as capable of defining articles of faith on matters not clearly derived from Scripture:

V. Of the Sufficiency of the Holy Scriptures for Salvation. The Holy Scripture containeth all things necessary to salvation; so that whatsoever is not read therein, nor may be proved thereby, is not to be required of any man that it should be believed as an article of faith, or be thought requisite or necessary to salvation...

Reformed churches

Presbyterian and Reformed churches also strongly reject papal infallibility. The Westminster Confession of Faith [2] which was intended in 1646 to replace the Thirty-Nine Articles, goes so far as to label the Roman pontiff "Antichrist"; it contains the following statements:

(Chapter one) IX. The infallible rule of interpretation of Scripture is the Scripture itself: and therefore, when there is a question about the true and full sense of any Scripture (which is not manifold, but one), it must be searched and known by other places that speak more clearly.

(Chapter one) X. The supreme judge by which all controversies of religion are to be determined, and all decrees of councils, opinions of ancient writers, doctrines of men, and private spirits, are to be examined, and in whose sentence we are to rest, can be no other but the Holy Spirit speaking in the Scripture.

(Chapter Twenty-Five) VI. There is no other head of the Church but the Lord Jesus Christ. Nor can the Pope of Rome, in any sense, be head thereof; but is that Antichrist, that man of sin, and son of perdition, that exalts himself, in the Church, against Christ and all that is called God.

Evangelical churches

Evangelical churches do not believe in papal infallibility for reasons similar to Methodist and Reformed Christians. Evangelicals believe that the Bible alone is infallible or inerrant. Most evangelical churches and ministries have statements of doctrine that explicitly say that the Bible, composed of the Hebrew Scriptures and the New Testament, is the sole rule for faith and practice. Most of these statements, however, are articles of faith that evangelicals affirm in a positive way, and contain no reference to the Papacy or other beliefs that are not part of evangelical doctrine.

Infallibility and temporal dogma at Vatican I

According to Raffaele De Cesare:

- The first idea of convening an Ecumenical Council in Rome to elevate the temporal power into a dogma, originated in the third centenary of the Council of Trent, which took place in that city in December, 1863, and was attended by a number of Austrian and Hungarian prelates.[45]

However, following the Austro-Prussian War, Austria had recognized the Kingdom of Italy. Consequently, because of this and other substantial political changes: "The Civiltà Cattolica suggested that the Papal Infallibility should be substituted for the dogma of temporal power ..."[46]

Moritz Busch's Bismarck: Some secret pages of his history, Vol. II, Macmillan (1898) contains the following entry for 3 March 1872 in pp. 43–44.

- Bucher brings me from upstairs instructions and material for a Rome despatch for the Kölnische Zeitung. It runs as follows: "Rumours have already been circulated on various occasions to the effect that the Pope intends to leave Rome. According to the latest of these the Council, which was adjourned in the summer, will be reopened at another place, some persons mentioning Malta and others Trient. [...] Doubtless the main object of this gathering will be to elicit from the assembled fathers a strong declaration in favour of the necessity of the Temporal Power. Obviously a secondary object of this Parliament of Bishops, convoked away from Rome, would be to demonstrate to Europe that the Vatican does not enjoy the necessary liberty, although the Act of Guarantee proves that the Italian Government, in its desire for reconciliation and its readiness to meet the wishes of the Curia, has actually done everything that lies in its power."

See also

- First Vatican Council

- Infallibility of the Church

- Papal supremacy

- Primacy of the Roman Pontiff

- Sola scriptura and free interpretation of Sacred Scripture

- Three-Chapter Controversy

- Union of Utrecht (Old Catholic)

- Lord Acton's dictum

Footnotes

- ↑ "infallibility means more than exemption from actual error; it means exemption from the possibility of error," P. J. Toner, Infallibility, Catholic Encyclopedia, 1910

- ↑ Erwin Fahlbusch et al. The encyclopedia of Christianity Eradman Books ISBN 0-8028-2416-1

- ↑ "Pope Has No Easy "Recipe" for Church Crisis", Zenit, 29 July 2005, retrieved 8 July 2009 [1]

- ↑ http://www.vatican.va/archive/catechism/p122a3p3.htm#II 551-553

- ↑ Ludwig Ott, Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma, Bk. IV, Pt. 2, Ch. 2, §6.

- ↑ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Vatican Council". http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/15303a.htm.

- ↑ Philip Magnus, Gladstone: A Biography (London: John Murray, 1963), pp. 235–6.

- ↑ Letter to the Duke of Norfolk in The Genius of John Henry Newman: Selections from His Writings. Ed. I. Ker. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- ↑ Stanley Jaki in Newman's Challenge p. 170

- ↑ John Paul II (1993-03-24). "General Audience Address of March 24, 1993". http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/audiences/alpha/data/aud19930324en.html.

- ↑ "Ordinatio Sacerdotalis: An Exercise of Infallibility". 1994-06-02. http://www.ewtn.com/library/ISSUES/ORDIN.TXT.

- ↑ Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger. "Concerning the Reply of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith on the Teaching Contained in the Apostolic Letter "Ordinatio Sacerdotalis"". http://www.catholicculture.org/library/view.cfm?recnum=5189.

- ↑ Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone. "Magisterial Documents and Public Dissent". http://www.catholicculture.org/library/view.cfm?recnum=7029.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Ratzinger, Cardinal Joseph; Bertone, Cardinal Tarcisio. "Doctrinal Commentary on the Concluding Formula of the Professio Fidei". http://www.ewtn.com/library/CURIA/CDFADTU.HTM.

- ↑ "CDF's Reply to a Doubt, approved by Pope John Paul II, in which the Congregation affirms that the doctrine of Ordinatio Sacerdotalis has been set forth infallibly". http://www.ourladyswarriors.org/teach/ordisace2.htm.

- ↑ What Think Ye of Rome? Part Four: The Catholic-Protestant Debate on Papal Infallibility, Christian Research Journal, Fall 1994, page 24

- ↑ John Harvey Treat, Johann Augustus Bolles, G. H. Houghton Butler, The Catholic faith, or, Doctrines of the Church of Rome contrary to scripture and the primitive church, pp. 480ff

- ↑ James Robert White, Answers to Catholic Claims, 104-8; Crowne Publications, Southbridge, MA: 1990

- ↑ petra: Rm. 8:33; 1Cor. 10:4; 1Pet. 2:8; lithos: Mat. 21:42; Mk.12:10-11; Lk. 20:17-18; Act. 4:11; Rm. 9:33; Eph. 2:20; 1Pet. 2:4-8; cf. Dt. 32:4, Is. 28:16

- ↑ Augustine, "On the Gospel of John," Tractate 12435, The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers Series I, Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1983, 7:450, as cited in White, Answers to Catholic Claims, p. 106

- ↑ John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, p. 1105; Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1960

- ↑ Ibid, Treat, Bolles, and Butler, pp. 479

- ↑ Ibid, Geisler and MacKenzie

- ↑ White, A Response to David Palm's Article on Oral Tradition from This Rock Magazine, May, 1995

- ↑ A Response to an Argument for Infallibility

- ↑ Richard Frederick Littledale, Plain reasons against joining the Church of Rome, pp. 157-59

- ↑ E.J.V. Huiginn, From Rome to Protestantism", The Forum, Volume 5, p. 111

- ↑ F. F. Bruce, Peter, Stephen, James and John, 86ff; Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1979

- ↑ Peter De Rosa, Vicars of Christ: the Dark Side of the Papacy

- ↑ E.J.V. Huiginn, From Rome to Protestantism", The Forum, Volume 5, pp. 111-113

- ↑ White, Of Athanasius and Infallibility

- ↑ James White, A Response to an Argument for Infallibility

- ↑ White, Exegetica: Roman Catholic Apologists Practice Eisegesis in Scripture and Patristics

- ↑ Ibid., Treat, Bolles, and Butler, pp. 486ff

- ↑ Harold O. J. Brown, Protest of a Troubled Protestant, New Rochelle, NY: Arlington House, 1969; p. 122

- ↑ Williston Walker, A History of the Christian Church, 3d ed. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1970; p. 67

- ↑ E.J.V. Huiginn, From Rome to Protestantism", The Forum, Volume 5, pp. 109-110

- ↑ p. 281, as cited in John E. Lynch's review of the work, in Church History, Vol. 42, No. 2. (Jun., 1973), pp. 279-280, at p. 279.

- ↑ Salmon, George (1914) The Infallibility of the Church John Murray pp.26-27

- ↑ Hasler, August Bernhard (1981). How the Pope Became Infallible: Pius IX and the Politics of Persuasion. Doubleday.

- ↑ Roger O'Toole, Review of "How the Pope Became Infallible: Pius IX and the Politics of Persuasion" by August Bernhard Hasler; Peter Heinegg, Sociological Analysis, Vol. 43, No. 1. (Spring, 1982), pp. 86-88, at p. 87.

- ↑ http://www.archive.org/stream/oppositioninfall00sparuoft/oppositioninfall00sparuoft_djvu.txt

- ↑ Encyclical of the Eastern Patriarchs of 1848

- ↑ Cleenewerck, Laurent. His Broken Body: Understanding and Healing the Schism between the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches. pp. 301-30

- ↑ De Cesare, Raffaele (1909). The Last Days of Papal Rome. Archibald Constable & Co.. p. 422.

- ↑ De Cesare, Raffaele (1909). The Last Days of Papal Rome. Archibald Constable & Co.. p. 423.

References

- Bermejo, Luis (1990). Infallibility on Trial: Church, Conciliarity and Communion. imprimi potest by Julian Fernandes, Provincial of India. ISBN 0-87061-190-9.

- Chirico, Peter. Infallibility: The Crossroads of Doctrine. ISBN 0-89453-296-0.

- The Last Days of Papal Rome by Raffaele De Cesare (1909) London, Archibald Constable & Co.

- Gaillardetz, Richard. By What Authority?: A Primer on Scripture, the Magisterium, and the Sense of the Faithful. ISBN 0-8146-2872-9.

- Hasler, Bernhard (1981). HOW THE POPE BECAME INFALLIBLE: Pius IX and the Politics of Persuation. Translation of Hasler, Bernhard (1979) (in German). WIE DER PAPST UNFEHLBAR WURDE: Macht und Ohnmacht eines Dogmas,. R. Piper & Co. Verlag.

- Küng, Hans. Infallible?: An inquiry. ISBN 0-385-18483-2.

- Lio, Ermenegildo (in Italian). Humanae vitae e infallibilità: Paolo VI, il Concilio e Giovanni Paolo II (Teologia e filosofia). ISBN 88-209-1528-6.

- McClory, Robert. Power and the Papacy: The People and Politics Behind the Doctrine of Infallibility. ISBN 0-7648-0141-4.

- O'Connor, James. The Gift of Infallibility: The Official Relatio on Infallibility of Bishop Vincent Gasser at Vatican Council I. ISBN 0-8198-3042-9 (cloth), ISBN 0-8198-3041-0 (paper).

- Powell, Mark E. Papal Infallibility: A Protestant Evaluation of an Ecumenical Issue. ISBN 978-0-8028-6284-6.

- Sullivan, Francis. Creative Fidelity: Weighing and Interpreting Documents of the Magisterium. ISBN 1-59244-208-0.

- Sullivan, Francis. The Magisterium: Teaching Authority in the Catholic Church. ISBN 1-59244-060-6.

- Tierney, Brian. Origins of Papal Infallibility, 1150-1350: A Study on the Concepts of Infallibility, Sovereignty and Tradition in the Middle Ages. ISBN 90-04-08884-9.

External links

- Online Version of the book THE TRUE AND THE FALSE INFALLIBILITY OF THE POPES (1871) by Bishop Joseph Fessler (1813-1872), Secretary-General of the First Vatican Council.

- Universal Catechism of the Catholic Church on Infallibility (Holy See official website)

"Infallibility". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

"Infallibility". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Infallibility". Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Infallibility". Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.- [3] News article from the Catholic Register on "Rethinking Papal Infallibilty".